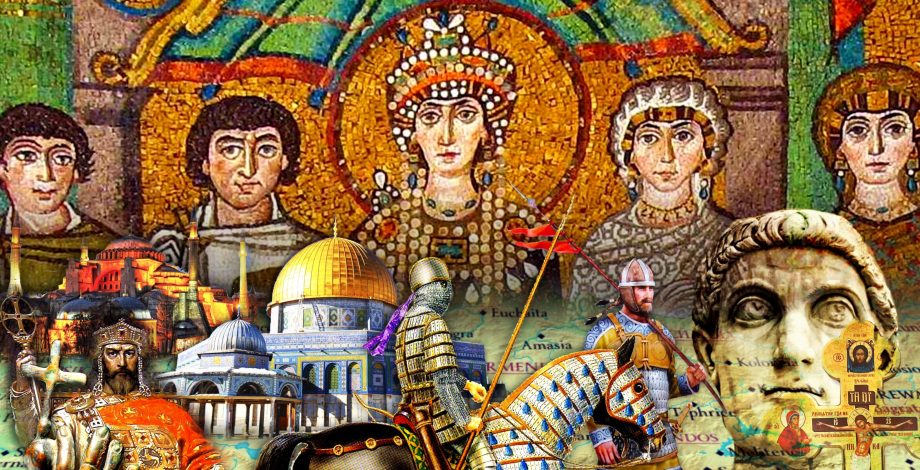

The Empress Irene becomes Regent for her son Constantine VI and sets about securing their rule. She manages to gain the support of the bureaucracy, army and church. Then she organises another Ecumenical Council to restore the Icons.

Period: 780-787

Download: A New Helena

RSS Feed: The History of Byzantium

If you want to send in feedback to the podcast:

– Either comment on this post.

– Or on the facebook page.

– Leave a review on Itunes.

– Follow me on Twitter.

Unable to download Episode 78 from iTunes

Still? It’s there.

Got it. Thank you.

Fantastic episode. Thank you.

An interesting episode. I haven’t listened to the ones that come later, so perhaps it’s addressed, but I did want to comment on the iconophile/iconoclast debate. It seemed to be implied in the podcast that icons were a newer innovation in the church. Archaeological evidence has proven otherwise, particularly with the house church as Dura Europos, established between 233 and 256, with frescoes of the Good Shepherd and the Healing of the Paralytic, among others. They may not be ‘traditional’ icons, but are at least proto-typical. Not to mention the higher-quality frescoes at the Jewish synagogue at Dura Europos indicates that iconography has its roots in Jewish religious art. Hardly a later Byzantine innovation.

Apologies for my lack of precision. I was referring to the portable icons only really. And their dissemination into local churches and people’s homes. As far as I remember this was traced to the second half of the 6th century.

That does make a little sense. I’m still not sure how the difference between portable icons and wall icons can effect the meaning that came across in the podcast. The key is that the veneration of icons, no matter their type, is likely of ancient origin and not a later innovation.

Well I did say in the introduction to Iconoclasm that the Pagan worship of statues/images was something Christians were keen to distance themselves from. And yet the emergence of Christian iconography suggests that the cultural desire for religious objects may have been reborn in this guise. And I’m happy to concede that the veneration of individual holy objects or relics did exist before the later 6th century. But the specific proliferation of icons and a common cultural acceptance of them as an everyday part of Christian faith has been connected to a specific period in Byzantine history. Please do check out Haldon/Brubaker “Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era” for more info.

I’ve just listened to this episode. Great work as always. One nitpick: You state that the iconophiles didn’t really have a biblical or theological argument against the iconoclasts. I think it’s evident, both from the declaration of the 2nd council of Nicaea, and also the writings of John of Damascus and Theodore the Studite, that they certainly did. The iconophiles’ had two central arguments, which I’m surprised go unmentioned: one is that the incarnation of Christ, as a true human inseparably united to his divine nature, made it possible to depict God in a way previously impossible and forbidden. The incarnation also restored human nature in general, allowing the portrayal of saints as reflections of Christ’s glory. The second key point is the distinction made between dulia and latreia (usually translated as “veneration” and “adoration/worship”.) The latter was proper to God alone, the former a relative glory offered to icons, saints, relics, etc. Both these points are central to the council’s decree. The iconophiles also made an important biblical point which I think is often overlooked- yes, the 2nd commandment, on its face, seems to ban any kind of representation, but later on, in the same book of Exodus, God commands Moses to decorate the ark with images of cherubim. Taking this into consideration, it stands to reason that the 2nd commandment could not be read as a flat prohibition of all religious images.

Hi, thanks for posting. Theological discussions on the podcast are always tricky. Its difficult to be precise when summarising such complex issues. On the podcast I didn’t attempt to get into arguments made by contemporary theologians. I just tried to discuss the tactics of the two sides at the Ecumenical Council.

What I said (according to my script) is: “The Iconophiles didn’t really have a biblical argument to support their position. Icons had only came to prominence in the last couple of centuries. So obviously there was no mention of them in the Holy Scripture nor any comment on them from the great church fathers of earlier centuries.”

Your argument about God’s instruction to Moses did not come up in the literature I read, so I credit you with your learning.