As we look back at Byzantium I turned once more to Professor Anthony Kaldellis. I asked him to present a list of ten influential East Romans who were not featured heavily in the political narrative.

Anthony Kaldellis is a Professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Chicago. He is the author of over a dozen books on Byzantium including the definitive history (The New Roman Empire: A History of Byzantium). Find out more here.

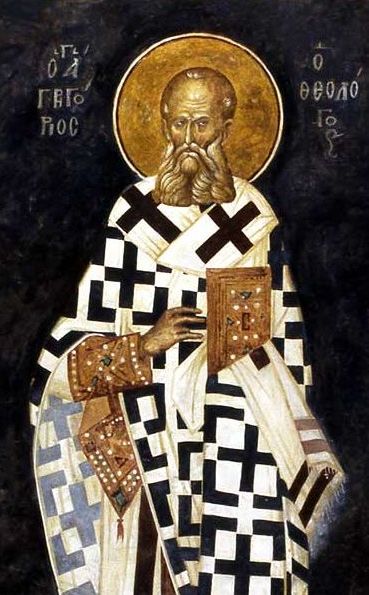

Pic: Gregory of Nazianzus, fresco from the Chora Church

Timestamps:

Gregory of Nazianzus: 6m 10s – 21m 12s

John Chrysostom: 21m 12s – 38m 12s

Tribonian: 38m 12s – 52m 40s

Anthemius of Tralles: 52m 40s – 1h 02m

Theodore the Studite: 1h 02m – 1h 15m

Stream: 10 Influential East Romans with Anthony Kaldellis. Part 1

Download: 10 Influential East Romans with Anthony Kaldellis. Part 1

RSS Feed: The History of Byzantium

If you want to send in feedback to the podcast:

– Either comment on this post.

– Or on the facebook page.

– Leave a review on Itunes.

A thoroughly enjoyable episode, and now that we’ve completed the narrative, it’s nice to be able to put such figures in historical context.

I have enjoyed the interview with Professor Anthony Kaldellis. His knowledge of the East Roman Empire is far wider than most byzantinists nowadays. And it’s always fun to listen to his passionate opinions and his witty remarks on those people he deals with. He is both scholarly and entertaining.

However, I am not totally sure he is impartial when he deals with certain people, mainly ecclesiastics and saints. He tends to judge them harshly and always tries to find their faults. For instance, in this interview, it is obvious that he doesn’t like the very clergymen he has picked out for his list of the 10 influential East Romans (Gregory of Nazianzus, John Chrysostom and Theodore the Studite) while it is also clear that he admires Anthemios of Tralles and Tribonian.

Of course, being an ecclesiastic doesn’t imply being a saint, and becoming a saint doesn’t imply being perfect either. Christian saints were human beings, made mistakes, had their contradictions, etc., like everybody else. But they took their beliefs very seriously indeed, and believed they were following the right path to be good Christians. Their own contemporaries, even those who were their enemies, knew that these men were outstanding Christians. Who are we to judge the way people in the past behaved, reacted, thought and even prayed?

Professor Kaldellis is probably right when he states that Theodore the Studite, for example, would be unbearable to most of us today; but, in the VII and VIII centuries, his behaviour and ideas would arguably be recognised as those of a real Christian, a wise man and a saint. Are we right and they are wrong? Well, they perceived the world very differently to the way we do; in order to understand them, we need to put ourselves in their shoes.

Regarding the issue of Theodore the Studite and iconoclasm, some scholars, among them Professor Kaldellis, believe that only Theodore the Studite and a tiny minority of the population of the East Roman Empire was really concerned about iconoclasm. I do not pretend to know more about Byzantium than them; I am just an amateur in comparison; however, I would like to point out that, even though most people were simple believers and did not know much about the complexities of Christian theology, they knew more about being a Christian than our secularised XXI century minds would like to think. Religion was so important for most people in that period that anything related to religion became a matter of life and death; and it makes sense because for them eternal salvation or condemnation depended on following the right Christian path. It is true that most Christians were illiterate but that didn’t prevent them from attending mass nor listening to what their parish priests, local monks and/or bishops thought about any controversial theological points.

I agree that iconoclasm was not the most important matter in the Christian agenda. The ideas debated in Nicaea I, Constantinople I, Ephesus and Chalcedon were clearly much more fundamental from a doctrinal point of view. But we ought to understand that the way you relate to a religious image if you are a good Christian is also quite an important aspect within the Christian doctrine. Deciding whether it was sacrilegious or not to worship or venerate religious images, whether Jesus Christ, Mary, the apostles and the saints could be painted or not, etc. must have caused a lot of anxiety to many good Christians (illiterate or not), and not only to monks like Theodore the Studite.

poi

I have enjoyed the interview with Professor Anthony Kaldellis. His knowledge of the East Roman Empire is far wider than most byzantinists nowadays. And it’s always fun to listen to his passionate opinions and his witty remarks on those people he deals with. He is both scholarly and entertaining.

However, I am not totally sure he is impartial when he deals with certain people, mainly ecclesiastics and saints. He tends to judge them harshly and always tries to find their faults. For instance, in this interview, it is obvious that he doesn’t like the very clergymen he has picked out for his list of the 10 influential East Romans (Gregory of Nazianzus, John Chrysostom and Theodore the Studite) while it is also clear that he admires Anthemios of Tralles and Tribonian.

Of course, being an ecclesiastic doesn’t imply being a saint, and becoming a saint doesn’t imply being perfect either. Christian saints were human beings, made mistakes, had their contradictions, etc., like everybody else. But they took their beliefs very seriously indeed, and believed they were following the right path to be good Christians. Their own contemporaries, even those who were their enemies, knew that these men were outstanding Christians. Who are we to judge the way people in the past behaved, reacted, thought and even prayed?

Professor Kaldellis is probably right when he states that Theodore the Studite, for example, would be unbearable to most of us today; but, in the VII and VIII centuries, his behaviour and ideas would arguably be recognised as those of a real Christian, a wise man and a saint. Are we right and they are wrong? Well, they perceived the world very differently to the way we do; in order to understand them, we need to put ourselves in their shoes.

Regarding the issue of Theodore the Studite and iconoclasm, some scholars, among them Professor Kaldellis, believe that only Theodore the Studite and a tiny minority of the population of the East Roman Empire was really concerned about iconoclasm. I do not pretend to know more about Byzantium than them; I am just an amateur in comparison; however, I would like to point out that, even though most people were simple believers and did not know much about the complexities of Christian theology, they knew more about being a Christian than our secularised XXI century minds would like to think. Religion was so important for most people in that period that anything related to religion became a matter of life and death; and it makes sense because for them eternal salvation or condemnation depended on following the right Christian path. It is true that most Christians were illiterate but that didn’t prevent them from attending mass nor listening to what their parish priests, local monks and/or bishops thought about any controversial theological points.

I agree that iconoclasm was not the most important matter in the Christian agenda. The ideas debated in Nicaea I, Constantinople I, Ephesus and Chalcedon were clearly much more fundamental from a doctrinal point of view. But we ought to understand that the way you relate to a religious image if you are a good Christian is also quite an important aspect within the Christian doctrine. Deciding whether it was sacrilegious or not to worship or venerate religious images, whether Jesus Christ, Mary, the apostles and the saints could be painted or not, etc. must have caused a lot of anxiety to many good Christians (illiterate or not), and not only to monks like Theodore the Studite.